What Is Portal Vein Thrombosis?

Portal vein thrombosis (PVT) happens when a blood clot blocks the portal vein - the main vessel that carries blood from your intestines to your liver. It’s not rare, especially in people with liver disease, cancer, or inherited clotting disorders. The clot can be partial or complete, and it can show up suddenly (acute) or develop slowly over time (chronic). Acute PVT is more treatable. Chronic PVT often leads to complications like portal hypertension, where pressure builds up in the liver’s blood vessels, causing fluid buildup, enlarged veins in the esophagus, and even life-threatening bleeding.

Back in 1868, German pathologist Rudolf Virchow figured out the three main reasons blood clots form: slow blood flow, damaged blood vessel walls, and blood that’s too prone to clotting. Today, we still use that framework. In PVT, the cause is often something else - like cirrhosis, liver cancer, recent abdominal surgery, or a genetic clotting condition. About 25-30% of non-cirrhotic patients have an underlying clotting disorder. If you’re over 50, have liver disease, or recently had an infection or surgery in your abdomen, your risk goes up.

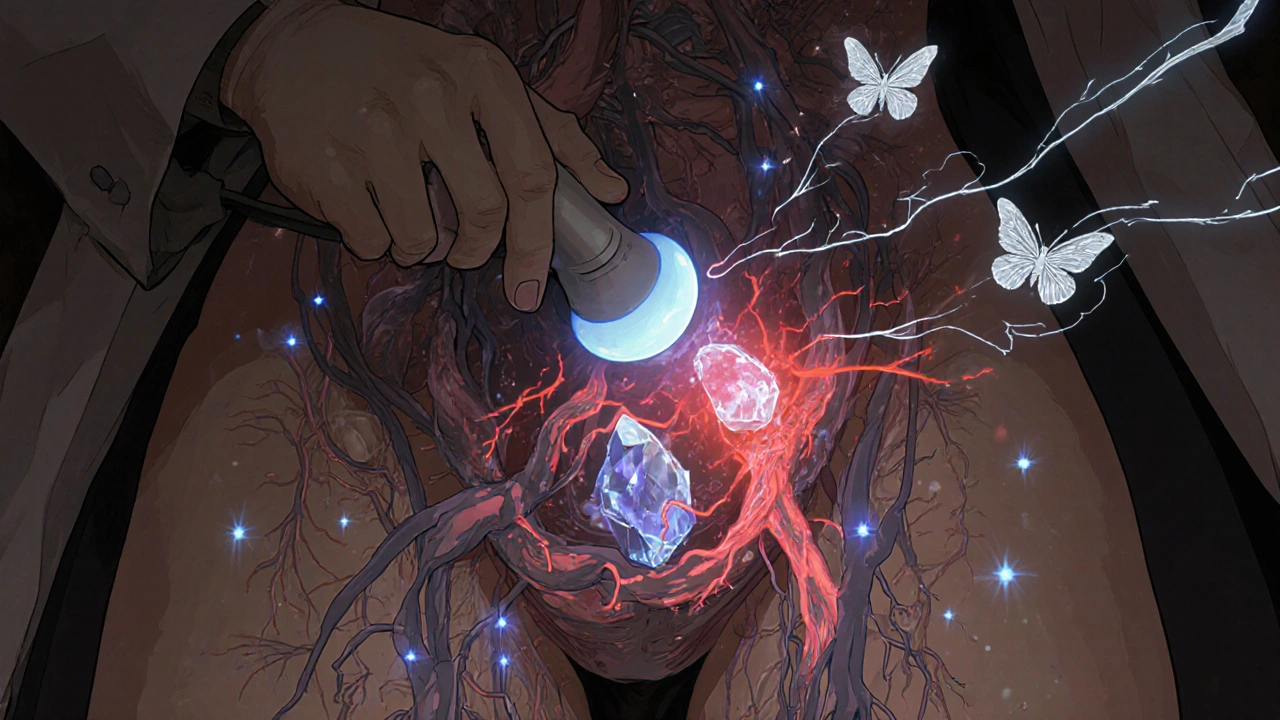

How Is Portal Vein Thrombosis Diagnosed?

Diagnosing PVT starts with imaging. The first test doctors use is a color Doppler ultrasound. It’s quick, safe, and detects portal vein blockages with 89-94% accuracy. You’ll lie down, and a technician will move a probe over your abdomen. They’re looking for two things: whether blood is flowing through the portal vein and if the vein itself looks swollen or blocked. If the clot is fresh, the vein may still be visible. If it’s old, the vein might be gone - replaced by a tangled network of tiny vessels called cavernous transformation.

If the ultrasound is unclear, the next step is a CT scan or MRI with contrast. These give a clearer picture of how much of the vein is blocked and whether the clot has spread into the splenic or mesenteric veins. Doctors classify the blockage as:

- Minimally occlusive (less than 50% blockage)

- Partially occlusive (50-99% blockage)

- Completely occlusive (100% blockage)

Complete blockage is the most dangerous. It can cut off blood flow to parts of the bowel, leading to intestinal ischemia - a medical emergency. That’s why timing matters. The sooner you’re diagnosed, the better your chances of reversing the damage.

Before starting treatment, doctors also check your liver function with Child-Pugh and MELD scores. These tell you how advanced your liver disease is. If you have cirrhosis, your bleeding risk goes up. That affects whether you can safely take blood thinners.

Why Anticoagulation Is the Standard Treatment

For years, doctors were hesitant to use blood thinners in people with liver disease. The fear was bleeding. But research over the last decade has turned that thinking around. Now, major guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) say: if you have acute PVT and aren’t at high risk of bleeding, you should get anticoagulation.

Anticoagulation isn’t just about preventing the clot from getting bigger. It’s about making it go away. Studies show that when treatment starts within six months of diagnosis, 65-75% of patients see the clot fully or partially dissolve. That’s called recanalization. If you wait longer than six months, that number drops to 16-35%. In one 2023 study of 93 non-cirrhotic patients, those on direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) had a 65% recanalization rate. Those on warfarin? Only 45%.

Stopping the clot from spreading also prevents intestinal ischemia - a condition where the bowel doesn’t get enough blood. Without treatment, up to 22% of patients with delayed diagnosis develop this and die. With anticoagulation, that number falls to 5%.

Which Blood Thinners Work Best?

Not all anticoagulants are the same. Your doctor picks one based on your liver function, kidney health, and whether you have cancer or a clotting disorder.

Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) - like enoxaparin - is often the first choice, especially for cirrhotic patients. It’s given as a daily shot. Dosing is based on your weight: 1 mg/kg twice daily or 1.5 mg/kg once daily. It’s preferred in liver disease because it doesn’t rely on liver metabolism. It’s also easier to monitor - doctors check your anti-Xa levels to make sure you’re in the therapeutic range (0.5-1.0 IU/mL).

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) - like rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran - are now first-line for non-cirrhotic patients. They’re pills, not shots. Rivaroxaban 20 mg daily and apixaban 5 mg twice daily are standard. In a 2020 study, 65-75% of non-cirrhotic patients on DOACs had complete clot resolution. That’s much higher than warfarin. Plus, they don’t need frequent blood tests.

Warfarin - a vitamin K antagonist - is still used, especially in places where DOACs aren’t available. But it’s trickier. You need regular INR checks to keep it between 2.0 and 3.0. It interacts with food and other meds. For cirrhotic patients, it’s less reliable because the liver can’t make clotting factors properly. Studies show LMWH works better in this group.

Here’s a quick comparison:

| Drug Type | Examples | Best For | Recanalization Rate | Bleeding Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMWH | Enoxaparin | Cirrhotic patients (Child-Pugh A/B) | 55-65% | 5-12% |

| DOACs | Rivaroxaban, Apixaban | Non-cirrhotic patients | 65-75% | 2-5% |

| Warfarin | Warfarin | When DOACs/LMWH unavailable | 40-50% | 6-10% |

Important note: DOACs are not approved for Child-Pugh C cirrhosis. The FDA warns against using them in severe liver impairment. But new data from the 2024 AASLD update now supports DOACs in Child-Pugh B7 patients - a big shift.

Who Should NOT Take Blood Thinners?

Anticoagulation isn’t for everyone. You should avoid it if you’ve had a recent variceal bleed (within 30 days), have uncontrolled ascites, or have Child-Pugh C cirrhosis. In these cases, the risk of bleeding - especially from swollen veins in your esophagus - is too high.

Doctors handle this carefully. If you have cirrhosis and PVT, they’ll often do an endoscopy first to check for varices. If they find them, they’ll treat them with band ligation - a procedure that ties off the veins - before starting anticoagulation. UCLA’s 2022 study showed this cut major bleeding from 15% to just 4%.

Platelet count matters too. If your platelets are below 50,000/μL, you’re at higher bleeding risk. Some centers, like Mount Sinai, give a platelet transfusion to raise counts above 30,000/μL before starting LMWH. It’s not standard everywhere, but it’s a smart move in borderline cases.

How Long Do You Need Anticoagulation?

The length of treatment depends on why the clot happened.

- If it was caused by something temporary - like recent surgery or infection - you’ll usually take anticoagulants for at least 6 months.

- If you have a genetic clotting disorder (like Factor V Leiden), you’ll likely need it for life.

- If you have cancer, anticoagulation continues as long as the cancer is active.

Stopping too early is risky. In one study, patients who stopped after 3 months had a 30% chance of the clot coming back. Six months is the minimum. For many, it’s forever.

What If Anticoagulation Doesn’t Work?

Even with treatment, some clots don’t dissolve. If you still have symptoms after 3-6 months of anticoagulation, your doctor may consider other options.

TIPS (Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt) is a procedure where a metal tube is placed inside the liver to bypass the blocked vein. It works in 70-80% of cases. But it can cause hepatic encephalopathy - confusion or brain fog - in 15-25% of patients. It’s usually reserved for those with severe portal hypertension who don’t respond to meds.

Percutaneous thrombectomy uses a catheter to physically break up or suck out the clot. It gives immediate results - 60-75% recanalization - but it’s only available in big medical centers. It’s not for everyone, but it’s a lifeline for some.

Surgery to create a shunt is rare now. It’s invasive and carries high risks. Most centers only consider it if everything else fails.

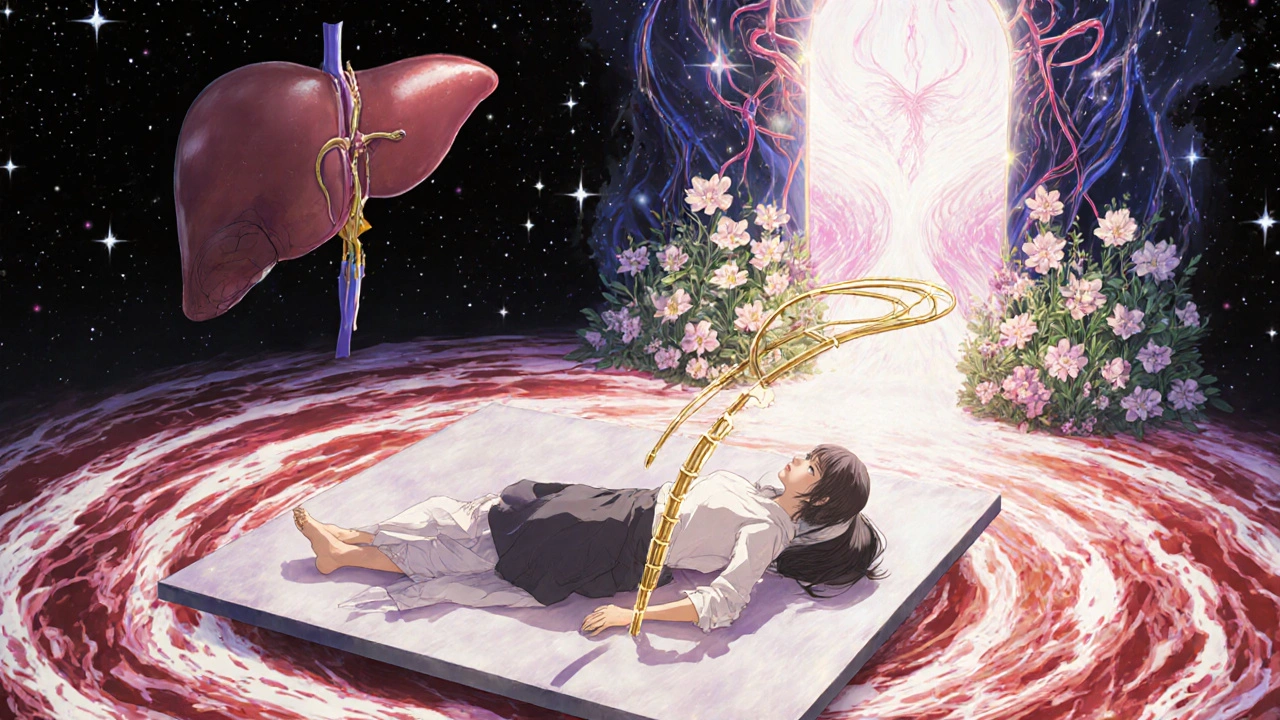

Special Cases: Liver Transplant Candidates

If you’re on a liver transplant list and have PVT, this changes everything. A large clot can disqualify you. But here’s the good news: anticoagulation improves your chances. A 2021 study found that patients who got anticoagulation before transplant had an 85% one-year survival rate. Those who didn’t? Only 65%.

At UCSF, anticoagulation reduced the number of patients excluded from transplant lists because of PVT from 22% to 8%. That’s huge. If you’re a transplant candidate, your team will work with a hepatologist and transplant surgeon to get you on the right treatment fast.

What’s New in 2025?

The field is moving fast. In 2023, the FDA approved andexanet alfa - a drug that can reverse the effects of rivaroxaban and apixaban in case of emergency bleeding. That’s a game-changer for safety.

The 2024 AASLD guidelines now include DOACs for Child-Pugh B7 patients, based on the CAVES trial showing they work just as well as LMWH. And a big 500-patient trial comparing rivaroxaban to enoxaparin in cirrhotic patients is expected to finish in late 2025.

There’s also a new drug called abelacimab in phase 2 trials. It targets a different part of the clotting system and could offer a safer option for people with liver disease.

By 2025, experts predict DOACs will be used in 75% of non-cirrhotic PVT cases and 40% of compensated cirrhotic cases. That’s up from 35% just two years ago.

Getting Started: What You Need to Do

If you’ve been diagnosed with PVT, here’s your action plan:

- Confirm the diagnosis with Doppler ultrasound - if it’s unclear, get a CT or MRI with contrast.

- Get your liver function tested - Child-Pugh and MELD scores will guide treatment.

- Have an endoscopy if you have cirrhosis - treat varices before starting blood thinners.

- Ask for a thrombophilia workup - especially if you’re under 50 and don’t have cirrhosis.

- Start anticoagulation as soon as possible - don’t wait.

- Work with a hepatologist or liver specialist - this isn’t something your general doctor should manage alone.

Don’t delay. Every week without treatment lowers your chance of recovery. Early intervention saves lives - and livers.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Waiting to treat - even if you feel fine. PVT can silently damage your liver and gut.

- Using warfarin in cirrhosis without close monitoring - LMWH or DOACs are safer.

- Skipping variceal screening - bleeding can happen fast.

- Stopping anticoagulation too early - 6 months is the minimum, not the goal.

- Assuming DOACs are safe in severe liver disease - they’re not approved for Child-Pugh C.

Can portal vein thrombosis be cured?

Yes, in many cases. With early anticoagulation, 65-75% of patients see the clot dissolve completely or partially. Recanalization is most likely when treatment starts within six months. Chronic PVT is harder to reverse, but anticoagulation still prevents worsening and complications like intestinal ischemia.

Is anticoagulation safe if I have cirrhosis?

It can be, but only if your liver function is mild to moderate (Child-Pugh A or B). LMWH or DOACs are preferred over warfarin. Before starting, doctors check for varices and treat them with band ligation. Bleeding risk is higher in cirrhosis - around 5-12% - but it’s still lower than the risk of letting the clot grow. Avoid anticoagulation if you have Child-Pugh C cirrhosis or recent bleeding.

Do I need lifelong anticoagulation?

Not always. If your PVT was caused by a temporary issue like surgery or infection, you’ll likely need 6 months. But if you have a genetic clotting disorder (like Factor V Leiden), cancer, or recurrent clots, you’ll probably need to stay on blood thinners for life. Your doctor will test for these factors and adjust your treatment plan accordingly.

What are the signs that PVT is getting worse?

Watch for sudden abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fever, or bloody stools - these could mean intestinal ischemia. If you have cirrhosis, new or worsening swelling in your belly, confusion, or vomiting blood could signal variceal bleeding. Any of these need emergency care.

Can I take over-the-counter painkillers with anticoagulants?

Avoid NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen - they increase bleeding risk. Use acetaminophen (Tylenol) instead, but don’t exceed 2,000 mg per day if you have liver disease. Always check with your doctor before taking any new medication, including supplements like fish oil or garlic pills, which can thin your blood too.

How often do I need follow-up scans?

Most doctors recommend a repeat Doppler ultrasound at 3 months to check if the clot is shrinking. Then again at 6 months. If you’re on long-term anticoagulation, you’ll need imaging every 1-2 years to monitor for recurrence. Blood tests (INR, platelets, liver enzymes) are checked every 1-3 months, depending on your meds and liver function.

Next Steps: What to Do Now

If you’re diagnosed with PVT, don’t wait. Talk to your doctor about starting anticoagulation. Ask if you need an endoscopy. Request a thrombophilia panel. Find a hepatologist if you don’t already have one. The sooner you act, the better your odds of avoiding long-term damage. This isn’t a condition you can ignore - but with the right treatment, it’s manageable, reversible, and survivable.

Noah Fitzsimmons

November 21, 2025 AT 22:25Oh wow, another ‘modern medicine is magic’ article. Let me guess - you skipped the part where 40% of these patients end up with portal hypertension anyway, and now they’re on lifelong anticoagulants just to avoid dying from a clot they didn’t even cause. Classic. I’ve seen this play out in my uncle’s liver clinic - they start the DOACs, he stops taking them because ‘he feels fine,’ and six months later, he’s in the ER with a mesenteric infarction. No one tells you that ‘recanalization’ is just a fancy word for ‘maybe we got lucky.’

Eliza Oakes

November 21, 2025 AT 23:26Hold up - so we’re now telling people with cirrhosis to take DOACs? The same DOACs that the FDA explicitly says aren’t approved for Child-Pugh C? And you’re calling this ‘evidence-based’? I’ve got a 72-year-old patient on rivaroxaban who’s got a MELD of 18 and ascites, and her INR’s been all over the place. You think a pill is safer than a shot? Please. This is just Big Pharma’s new cash cow dressed up as progress. LMWH has been the gold standard for decades - why are we pretending the new stuff is better when the data’s still messy?

Clifford Temple

November 23, 2025 AT 05:16Let’s be real - this whole ‘anticoagulation for PVT’ thing is just another way for the medical-industrial complex to keep Americans on pills forever. In my country, we don’t need fancy blood thinners. We use garlic, turmeric, and prayer. And guess what? Our liver transplant rates are higher than yours. Why? Because we don’t treat every little clot like it’s the end of the world. You people are so scared of clots you’re turning healthy people into drug addicts. This isn’t medicine - it’s fear-based marketing.

Corra Hathaway

November 25, 2025 AT 02:05Y’ALL. I just read this whole thing and I’m SO EMOTIONALLY MOVED 😭❤️🩹 Like… who knew a vein could be so dramatic?! But seriously - THIS IS HOPE. If you’ve been diagnosed with PVT, YOU ARE NOT ALONE. There’s a whole world of doctors, researchers, and people like you who are fighting this. And guess what? You CAN beat it. Start the meds. Get the scan. Talk to your hepatologist. You got this!! 💪🩺✨ #PVTWarrior #AnticoagulationIsLife #LiverLove

Shawn Sakura

November 26, 2025 AT 13:58Just wanted to say thank you for this incredibly detailed and well-structured post. I'm a med student and this is exactly the kind of clinical summary I need to study for my hepatology rotation. One tiny typo though - 'recanalization' is misspelled as 'recanalization' in the first paragraph under 'Why Anticoagulation Is the Standard Treatment' - just a heads up! 😊

Paula Jane Butterfield

November 27, 2025 AT 14:19As someone who grew up in rural India and now works in a US hospital, I’ve seen how PVT is treated differently across cultures. In my village, they’d use herbal decoctions and wait. Here, we hit it with anticoagulants within 48 hours. Both have their place. But I’ll say this - if you’re a non-cirrhotic patient under 50 with no clear trigger, DO the thrombophilia panel. My cousin had Factor V Leiden and didn’t know until she had a second clot after pregnancy. This isn’t just about the liver - it’s about your whole clotting system. Don’t skip the labs.

Simone Wood

November 29, 2025 AT 04:26Let’s not pretend DOACs are benign. The CAVES trial? Small cohort. Retrospective. And you’re already citing 2024 AASLD updates like they’re gospel. Meanwhile, the bleeding rates in cirrhotics are still 5-12% - that’s not ‘safe,’ that’s statistically significant risk. And don’t get me started on the fact that 30% of patients who stop anticoagulation at 3 months re-thrombose. This isn’t a cure - it’s a life sentence with side effects. We’re treating a symptom, not the root cause. And the root cause? Often, it’s systemic inflammation from poor diet, alcohol, or metabolic syndrome. But no - let’s just give them pills and call it a day.

Swati Jain

December 1, 2025 AT 02:14Wow, this is actually one of the most coherent PVT summaries I’ve seen in English. But let’s be real - in India, we don’t even have access to DOACs in 70% of hospitals. We’re stuck with warfarin and monthly INRs. And patients? They stop because it’s expensive, or they forget, or they think ‘if I feel fine, I don’t need it.’ So your 65% recanalization rate? That’s in academic centers with nurses calling patients every week. In the real world? Maybe 25%. This article reads like a glossy brochure for a pharma conference. But still - good info. Just… context matters.

Florian Moser

December 2, 2025 AT 07:15This is an excellent, thorough overview. One point that deserves more emphasis: the 6-month window for anticoagulation is critical. Delaying treatment doesn’t just reduce recanalization rates - it increases the likelihood of cavernous transformation, which makes future interventions like TIPS far less effective. Early diagnosis and prompt initiation are not just ideal - they’re the difference between a manageable condition and a lifelong burden. Also, always rule out malignancy in patients over 50 with unexplained PVT. It’s more common than people think.

jim cerqua

December 2, 2025 AT 23:05Okay, so let me get this straight - we’re giving people with liver disease blood thinners because we’re scared of a clot… but we’re not scared of the fact that 1 in 5 of them will bleed out because we didn’t check their varices first? And then we pat ourselves on the back because we ‘reduced bleeding from 15% to 4%’? That’s not progress - that’s damage control. And what about the 15-25% who get hepatic encephalopathy after TIPS? You call that ‘a lifeline’? I call it trading one hell for another. This isn’t medicine - it’s triage with a side of optimism.

Donald Frantz

December 4, 2025 AT 10:16Interesting data. But I’m curious - what’s the long-term mortality data? You cite recanalization rates and bleeding risks, but what’s the 5-year survival difference between treated vs. untreated? And are we accounting for quality of life? Are patients on DOACs more likely to be hospitalized for GI bleeds, or to develop cognitive issues from microbleeds? Also, what’s the cost per QALY? I’m not saying the treatment isn’t valuable - I just want to see the full picture, not just the headline stats.

Sammy Williams

December 5, 2025 AT 03:16man this is wild i just got diagnosed with pvt last week and was totally lost but this post literally saved me. i’m gonna get the ultrasound, ask for the endoscopy, and talk to a hepatologist tomorrow. thanks for writing this. seriously.

Julia Strothers

December 7, 2025 AT 01:49Let’s be honest - this whole ‘anticoagulation for PVT’ push is part of a larger agenda. Did you know the FDA approved andexanet alfa the same week that DOAC sales hit $12 billion? Coincidence? I think not. The liver transplant industry wants more candidates - but they don’t want you to know that anticoagulation is being pushed to artificially inflate transplant eligibility. And the ‘cavernous transformation’ they mention? That’s not a natural progression - that’s what happens when you force blood flow through damaged vessels. They’re creating disease to sell treatment. Wake up.