When a brand-name drug loses its patent, the race to be the first generic version on the market isn’t just about speed-it’s about locking in market share for years. The first company to file for FDA approval and successfully challenge the patent doesn’t just get a head start. It gets a near-monopoly on sales for months, and often, a lasting edge that lasts long after the exclusivity period ends.

Why Being First Matters More Than You Think

The Hatch-Waxman Act is a 1984 U.S. law that created the legal pathway for generic drugs to enter the market while protecting brand-name drug innovation. One of its most powerful tools is the 180-day marketing exclusivity period granted to the first generic manufacturer that successfully challenges a brand drug’s patent.This isn’t just a reward-it’s a strategic advantage. During those 180 days, no other generic can legally sell the same drug. That means the first mover captures nearly all of the demand. And because pharmacists and prescribers don’t like switching inventory or prescribing habits, that initial dominance doesn’t vanish when the exclusivity ends.

Studies show the first generic typically grabs 70-80% of the generic market during its exclusivity window. Even after three or four other generics enter, it still holds 30-40% of sales. Second entrants? They’re lucky to hit 15%. Later players often struggle to break 10%. This isn’t luck. It’s system inertia.

The Hidden Rules of Pharmacy Stocking

Pharmacies don’t stock every generic version of a drug. They pick one. Usually, the first one that arrived. Why? Inventory costs. Training staff. Reconciling prescriptions. It’s easier to stick with what’s already working.This creates a massive barrier for competitors. Even if your generic is cheaper, better packaged, or has the same active ingredient, if the pharmacy already stocks the first version, they’re not going to switch unless forced. And patients? They rarely ask for a different generic. If their prescription fills without issue, they don’t care who made it.

That’s why a first-mover with even a one-month lead over the next competitor can end up with a 10-point market share advantage. A three-year gap? That’s a nearly untouchable position. McKinsey found that in some cases, the first generic holds over 90% market share years later-not because it’s the best, but because it was the first.

Not All Drugs Are Created Equal

The strength of the first-mover advantage depends heavily on the type of drug.Injectables and inhalers? Huge advantage. These are complex to manufacture. Fewer companies can make them. That means fewer challengers. First movers in this space often hold 15-20 percentage points above fair market share.

Oral pills? Less so. Thousands of companies can make a simple tablet. Competition floods in fast. The advantage shrinks to 6-8 points. In crowded markets with five or more generics, the first mover’s lead fades quickly-sometimes within 18 months.

Therapeutic area matters too. Drugs for chronic conditions-like high blood pressure, diabetes, or depression-are stickier. Patients take them for years. They don’t switch unless something goes wrong. First movers in these areas see the longest-lasting advantages.

On the flip side, short-term meds like antibiotics? Less impact. Patients don’t form loyalty. Pharmacists rotate brands freely. First-mover advantage here is weak or nonexistent.

Who Wins? Big Companies vs. Smaller Players

Size matters. Large generic manufacturers with global supply chains, regulatory teams, and legal departments have a clear edge.They can afford to file patent challenges years in advance. They have the resources to prepare manufacturing lines before the patent even expires. They can negotiate bulk deals with API suppliers, cutting costs by 12-15% compared to smaller firms.

Smaller companies? They often struggle. Even if they’re first to file, they may lack the capacity to scale production fast enough. Or they can’t handle FDA inspections. Or they miss a filing deadline. The result? They win the race but lose the market.

McKinsey found that large pharma first movers gain more than 10 market-share points over fair share. Smaller players? Often underperform. They get the exclusivity but fail to capture the market.

The Big Threat: Authorized Generics

The biggest surprise for many first movers? The brand company isn’t sitting idle.During the 180-day exclusivity window, the original drugmaker can launch an Authorized Generic is a version of the brand drug sold under a generic label, usually by the brand company itself or a partner. It looks identical to the brand product but is priced like a generic.

This is a legal loophole. And it’s devastating. Instead of facing just one competitor, the first generic now faces two: the brand and the authorized generic. Retail prices drop 4-8%. Wholesale prices fall 7-14%. Revenue plummets.

The FTC estimates that authorized generics reduce first-filer profits by 20-30%. Many first movers have gone bankrupt because they didn’t plan for this. The smart ones? They build contingency plans. They lock in multiple API suppliers. They diversify their product pipeline. They don’t rely on one drug to carry them.

Timing Is Everything

Getting to market fast isn’t just about speed-it’s about precision.The average time from filing a patent challenge to launching a generic? 18 to 36 months. That’s a long runway. Companies that win are the ones who start planning five years ahead. They monitor patent expirations. They run bioequivalence studies early. They build manufacturing capacity before the patent even expires.

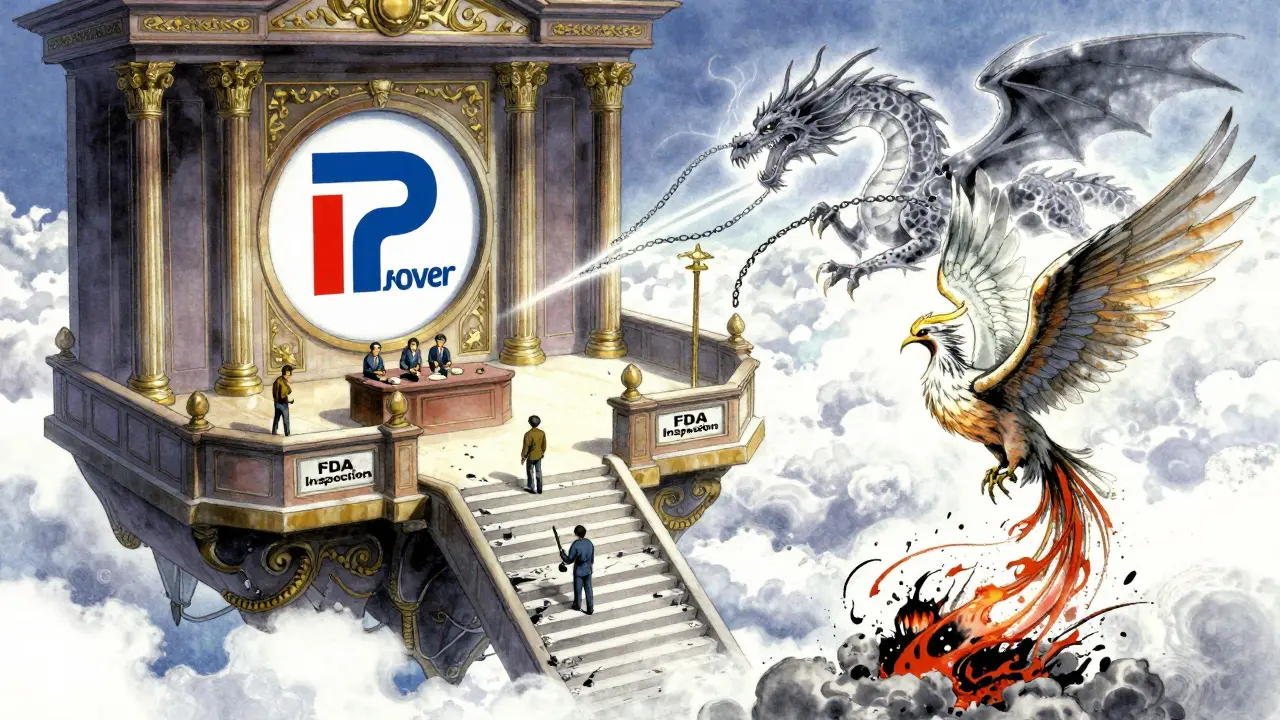

But timing also means avoiding delays. FDA inspections can take months. If your facility fails an audit, you lose your spot. One missed deadline, and you’re out. That’s why the most successful companies have dedicated regulatory teams-full-time people who live and breathe FDA requirements.

And then there’s the legal side. Patent challenges are lawsuits. They’re expensive. They’re risky. But they’re also the only way to trigger the 180-day exclusivity. Many companies hire specialized law firms just for this. It’s not a cost-it’s an investment.

What’s Changing Now?

The landscape is shifting.The FTC has cracked down on "pay-for-delay" deals-where brand companies pay first generics to delay entry. These deals used to slow down competition. Now, with enforcement tightening, first generics are entering the market 6-9 months faster on average.

Also, the FDA is pushing for faster reviews under GDUFA III. That sounds good, right? But it also means applications are more complex. Smaller companies struggle to keep up. The advantage is shifting even more toward big players with deep regulatory expertise.

Complex generics-like injectables, nasal sprays, and transdermal patches-are the new frontier. These are harder to copy. Fewer companies can make them. That means less competition. And bigger rewards for the first mover.

Is the Advantage Still Worth It?

Yes. Even with more competition, more regulation, and more threats, the first-mover advantage remains one of the most powerful forces in generic pharmaceuticals.Generic drugs now make up over 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. But they account for only 23% of total drug spending. That means the profit margin is razor-thin. The only way to make money is to be first.

That first generic launch is the moment the brand drug’s revenue collapses by 70-90%. Whoever captures the largest slice of that falling market wins. And because of how the system works-pharmacies, prescribers, patients, supply chains-it’s almost impossible to catch up.

Being first doesn’t guarantee success. But being second? Almost always means playing catch-up in a game you can’t win.

What is the 180-day exclusivity period for generic drugs?

The 180-day exclusivity period is a legal right granted under the Hatch-Waxman Act to the first generic manufacturer that successfully challenges a brand drug’s patent. During this time, no other generic can legally enter the market. This gives the first mover a monopoly on sales, allowing them to capture the majority of the generic market before competitors arrive.

Can a brand company compete with its own generic?

Yes. Brand companies can launch an Authorized Generic during the first mover’s 180-day exclusivity period. This is a version of the brand drug sold under a generic label, often at a lower price. While legal, it reduces the first mover’s profits by 20-30% by splitting the market with a nearly identical product.

Why do pharmacies stock only one generic version?

Pharmacies limit inventory to reduce costs and simplify operations. Stocking multiple generics of the same drug requires extra storage, training, and administrative work. Once a pharmacy starts using a particular generic, they stick with it unless forced to switch-giving the first mover a lasting edge.

Do small generic companies stand a chance?

It’s harder. Small companies often lack the resources to file patent challenges, prepare manufacturing lines, or pass FDA inspections on time. Even if they’re first to file, they may not be able to scale production fast enough. Large manufacturers with global supply chains and regulatory teams consistently outperform them.

How long does the first-mover advantage last?

It can last years. While the legal exclusivity ends after 180 days, the market advantage often persists due to prescriber habits, pharmacy stocking preferences, and patient loyalty. In many cases, the first generic still holds 30-40% of the market even after five or more competitors enter.

Are complex generics more profitable for first movers?

Yes. Complex generics-like injectables, inhalers, and transdermal patches-are harder and more expensive to develop. Fewer companies can make them, so competition is limited. First movers in these categories often capture 15-20 percentage points above fair market share, compared to 6-8 points for simple oral tablets.

Connie Zehner

December 20, 2025 AT 05:37Monte Pareek

December 20, 2025 AT 10:12Tim Goodfellow

December 22, 2025 AT 05:57holly Sinclair

December 23, 2025 AT 19:12Dikshita Mehta

December 24, 2025 AT 08:59Alex Curran

December 24, 2025 AT 20:46Dorine Anthony

December 24, 2025 AT 22:37Kathryn Featherstone

December 25, 2025 AT 12:58Mahammad Muradov

December 27, 2025 AT 10:25pascal pantel

December 28, 2025 AT 06:27Sahil jassy

December 28, 2025 AT 10:07Elaine Douglass

December 28, 2025 AT 13:07Nicole Rutherford

December 30, 2025 AT 12:38Chris Clark

December 31, 2025 AT 11:59Gloria Parraz

December 31, 2025 AT 18:48