When you're taking a new medication or joining a clinical trial, you might see the term serious adverse event in your paperwork. It sounds scary. And it should - because it's meant to flag real risks. But here's the thing most patients don't realize: serious doesn't mean severe. And that mix-up causes a lot of unnecessary panic.

What Exactly Is a Serious Adverse Event?

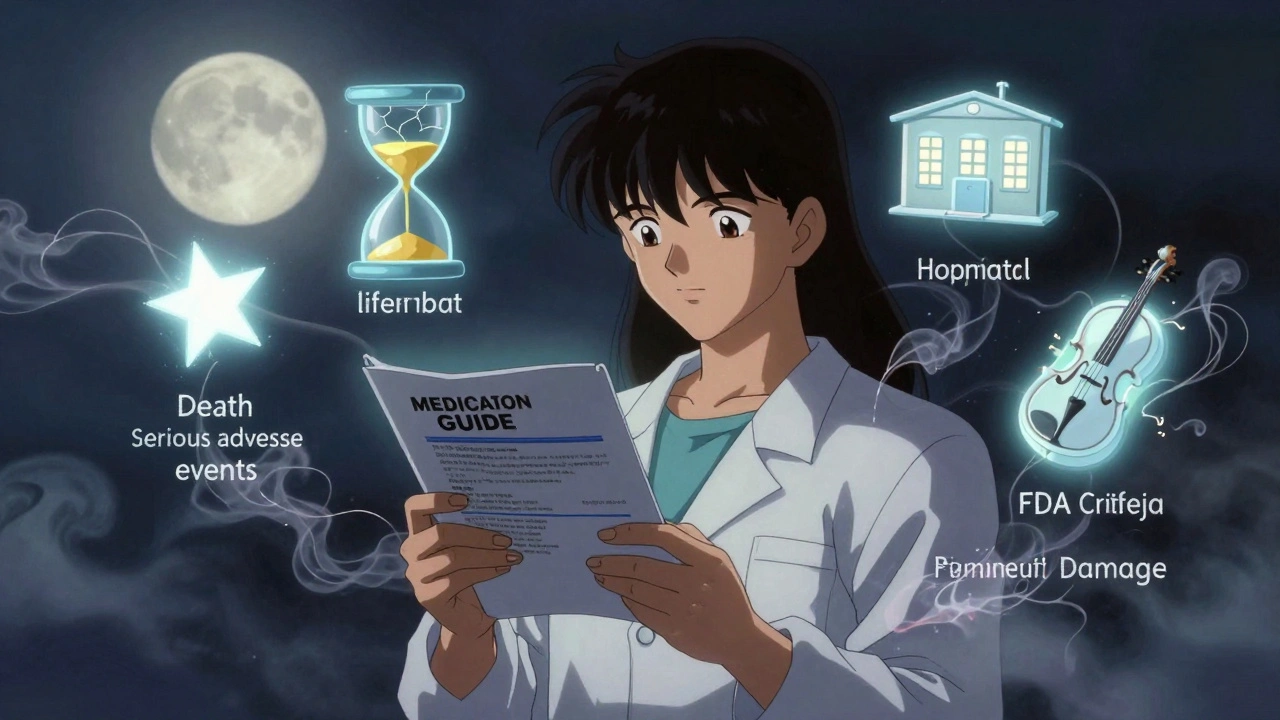

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines a serious adverse event (SAE) as any bad medical outcome that happens while you're using a drug, vaccine, or medical device - and it meets one of five specific, serious criteria. It doesn't matter if the event was caused by the product. If it hits one of these marks, it's serious. Here’s what counts:- Death - even if it’s just suspected to be linked to the treatment.

- Life-threatening - meaning you were in real danger of dying at the time it happened. Not just "could have been bad." You had to be actively at risk.

- Hospitalization - either you had to be admitted because of it, or your stay got extended by at least 24 hours.

- Disability or permanent damage - something that seriously messes with your daily life, like losing vision, nerve damage, or organ failure.

- Congenital anomaly - a birth defect in a baby whose parent took the medicine during pregnancy.

There’s also something called an "Important Medical Event" - a catch-all for situations that don’t fit the above but still need attention. Like a sudden heart rhythm problem that didn’t land you in the hospital but could’ve led to one. These are included too.

Why "Serious" Isn’t the Same as "Severe"

This is where most patients get tripped up. A lot of people think "serious" means "really bad symptoms." But that’s not how the FDA uses the word. Think of it this way: you might have a Grade 3 side effect - like severe nausea that makes you vomit all day and you need IV fluids. That’s intense. But if you don’t end up in the hospital, it’s not a serious adverse event under FDA rules. It’s severe, but not serious. On the flip side, you could have mild dizziness that doesn’t feel bad at all - but if it causes you to fall and break your hip, that’s a serious adverse event. The event itself wasn’t intense. The outcome was. The FDA made this distinction on purpose. They don’t want to flood doctors with every uncomfortable side effect. They want to focus on events that change your life - or end it.How the FDA Uses This Information

Every time a serious adverse event is reported during a clinical trial or after a drug hits the market, it goes into the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). That’s a giant database that helps them spot patterns. In 2022 alone, this system led to 128 safety alerts and 47 changes to drug labels - like adding new warnings about liver damage or heart risks. That’s not just paperwork. It’s what keeps you safe. The FDA doesn’t just wait for reports. They also use the Sentinel Initiative, which pulls data from 300 million electronic health records across the country. That means they can see if people on a certain drug are ending up in the hospital more often than expected - even before anyone files a formal report. And here’s something most patients don’t know: you can report an adverse event yourself. The FDA’s MedWatch program lets you fill out Form 3500B online. In 2022, over 38,000 reports came directly from patients - up 12% from the year before.

What You’ll See in Your Medication Guide

When you pick up a new prescription, the FDA requires the pharmacy to give you a Medication Guide. Look for the section called "Warnings and Precautions." That’s where they list the serious adverse events seen during testing. You might read something like: "Serious infections occurred in 2.3% of patients." That means out of every 100 people who took the drug, about 2 or 3 had an infection serious enough to meet FDA criteria - maybe they had to be hospitalized or got sepsis. In clinical trial consent forms, you’ll see similar language. But here’s the catch: many of these forms are written in dense legal jargon. A 2022 survey found that only 32% of patients understood what "serious adverse event" meant without extra explanation. That’s why the FDA is pushing for plain language. Starting in 2025, clinical trial registries will be required to include simplified summaries of serious events - things like "This drug may cause hospitalization due to liver problems" instead of "SAE: hepatotoxicity Grade 4."What Patients Are Saying

Real patients have shared their experiences online. One person on a cancer forum said they panicked when they saw "Grade 4 neutropenia" listed as an adverse event. They thought it meant they were in life danger. Their nurse explained: "That’s a severe drop in white blood cells. It’s common with your treatment, and we can fix it with a shot. It’s not serious unless you get a fever and end up in the hospital." Another patient with Type 1 diabetes said understanding that diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) counted as a serious event helped them know when to call 911 during their trial. "I didn’t realize hospitalization for DKA was the red flag," they wrote. "Now I know when to act." But the confusion still runs deep. A survey of 1,500 trial participants found that 78% mixed up "serious" and "severe." And 62% said they felt anxious even when side effects weren’t classified as serious - just because they felt intense.Where the System Falls Short

The FDA’s system works well - but it’s not perfect. Most reports come from doctors and hospitals. Patients rarely report side effects themselves unless they’re really sick. That means a lot of events go unnoticed - especially for people who don’t go to the hospital. Experts estimate that only 1% to 10% of all adverse events are ever reported. There’s also a known bias. Drug companies are required to report adverse events, but studies show they sometimes downplay them. One analysis found that industry reports missed 27% to 35% of serious events compared to independent reviews. And international standards don’t always match. What counts as serious in the U.S. might not count in Europe or Japan - especially when it comes to hospitalization. A 2021 study found that 23% of events flagged as serious by the FDA weren’t considered serious under Japanese rules.

What You Can Do

You don’t need to be an expert to protect yourself. Here’s how to use this knowledge:- Ask for the Medication Guide - don’t just take the pill. Read the section on "Warnings and Precautions."

- Know the five criteria - death, life-threatening, hospitalization, disability, birth defect. If something triggers one of these, it’s serious.

- Don’t panic over severe symptoms alone - if you’re nauseous or tired but not hospitalized, it’s probably not a serious event. Still, tell your doctor.

- Report your own side effects - if something feels wrong, even if you didn’t go to the hospital, file a report at MedWatch.

- Ask your provider - "Is this side effect serious under FDA guidelines?" or "Could this lead to hospitalization?"

The goal isn’t to scare you. It’s to help you recognize when something truly needs attention - so you can act fast, get help, and stay safe.

What’s Changing Soon

The FDA isn’t standing still. In 2023, they released a draft plan to make SAE reporting clearer for patients. By the end of 2024, they plan to launch a new patient education portal with simple videos, checklists, and real-life examples. They’re also using AI to sort through reports faster. A pilot program cut review time for critical events from 30 days to just 7. That means if a new drug starts causing unexpected liver damage, the FDA can warn doctors and patients quicker. And for the first time, patient voices are being built into the system. The FDA now asks patients: "What do you consider a serious side effect?" That input is shaping how new drugs are tested and labeled.Bottom Line

A serious adverse event isn’t about how bad you feel. It’s about what happened to your body - and whether it changed your life in a big way. Understanding this difference helps you make smarter decisions, ask better questions, and know when to get help - without wasting energy on fear that doesn’t fit the facts.When you’re told a side effect is "serious," it’s not a warning to stop everything. It’s a signal to pay attention - and talk to your doctor.

What’s the difference between a serious adverse event and a severe side effect?

A severe side effect means the symptoms are intense - like high fever, vomiting, or extreme fatigue. A serious adverse event is defined by an outcome: death, hospitalization, life-threatening condition, permanent damage, or birth defect. You can have a severe side effect that isn’t serious - like intense nausea that doesn’t land you in the hospital. And you can have a mild symptom - like dizziness - that leads to a fall and broken hip, making it serious.

Do all side effects get reported to the FDA?

No. Only serious adverse events are required to be reported by drug companies and healthcare providers. Mild or moderate side effects - even if they’re uncomfortable - don’t have to be reported unless they meet the FDA’s five criteria. Patients can report any side effect through MedWatch, but most reports come from doctors and hospitals.

Can I report a side effect myself?

Yes. The FDA’s MedWatch program lets patients report adverse events directly using Form 3500B. You can file online at the FDA’s website. In 2022, over 38,000 reports came from patients like you. Your report helps the FDA spot safety issues faster.

Why does my doctor say a side effect isn’t serious even though it felt terrible?

Because "serious" has a legal definition under FDA rules. If your side effect didn’t cause hospitalization, death, life-threatening risk, permanent damage, or a birth defect, it’s not classified as serious - even if it felt awful. For example, severe fatigue from chemotherapy is common and usually not serious unless it leads to dehydration and hospitalization. Your doctor is using the official standard, not downplaying how you feel.

How does the FDA know if a drug is unsafe based on these reports?

The FDA doesn’t react to single reports. They look for patterns. If 10 people report the same rare liver problem after taking a drug, that’s a signal. If 100 do, they investigate. They use data from millions of patients through the Sentinel Initiative to compare rates of hospitalizations and deaths between people taking the drug and those who aren’t. If the numbers are unusually high, they issue warnings, update labels, or pull the drug.

Are serious adverse events common with new drugs?

They’re rare. Most drugs are tested on thousands of people before approval, and serious events are usually caught then. But some only show up after millions use the drug - like a sudden heart rhythm issue that affects 1 in 10,000. That’s why post-market monitoring matters. About 1 in 5 new drugs get updated safety labels within the first two years after release because of new serious event reports.

Juliet Morgan

December 6, 2025 AT 09:44Okay but real talk-how many of us have been scared out of our minds by a ‘serious adverse event’ only to find out it just meant someone got a bad headache and went to the ER for an IV? I’ve been on meds that made me feel like I was dying, but the doctor just shrugged. Now I know why. Thanks for clarifying this.

Ada Maklagina

December 7, 2025 AT 05:07So dizziness that makes you fall and break your hip = serious

Severe nausea that leaves you curled up for 3 days = not serious

That’s wild.

Mark Ziegenbein

December 8, 2025 AT 15:57Let me be the first to say this: the FDA’s definition of ‘serious’ is a masterclass in bureaucratic semantics wrapped in the thin veneer of patient safety. The entire framework is predicated on a reductive, outcome-based taxonomy that ignores the lived experience of suffering-because god forbid we acknowledge that pain without hospitalization is still pain. We are reducing human vulnerability to a checklist. The fact that a patient can endure Grade 4 fatigue, vomiting, and neurological disruption but escape the ‘serious’ label because they didn’t end up in the ICU is not a triumph of precision-it’s a moral failure dressed in regulatory language. This isn’t science. It’s liability management masquerading as care.

Harry Nguyen

December 10, 2025 AT 08:33Of course the FDA defines serious as hospitalization. That’s because they’re not trying to protect you-they’re trying to protect Big Pharma from lawsuits. If you get cancer from a drug but don’t die, it’s not serious. If you break your hip falling off a curb after taking a pill, that’s serious. Logic? What logic?

Katie Allan

December 11, 2025 AT 02:42This is the kind of clarity we need more of. So many people panic over side effects that are uncomfortable but not dangerous, and others dismiss real red flags because they ‘don’t feel bad enough.’ Understanding this distinction isn’t just helpful-it’s lifesaving. Thank you for breaking it down without jargon.

James Moore

December 11, 2025 AT 03:19It is, without a doubt, a profound and deeply troubling epistemological paradox that the medical-industrial complex has codified suffering into a bureaucratic taxonomy wherein the severity of subjective experience is rendered irrelevant unless it results in institutional intervention-hospitalization, death, or permanent anatomical alteration. Thus, the silent, invisible, and excruciating torment of chronic fatigue, debilitating vertigo, or psychological dissociation-symptoms that render daily life untenable-is rendered ‘non-serious’ by virtue of its failure to meet the arbitrary threshold of institutionalization. This is not medicine. This is administrative nihilism.

Kylee Gregory

December 12, 2025 AT 17:19I think what’s really important here is that both sides matter-the patient’s experience and the regulatory definition. Just because something isn’t classified as ‘serious’ doesn’t mean it’s not real. And just because something is classified as ‘serious’ doesn’t mean it’s inevitable. It’s about awareness, not fear.

Laura Saye

December 12, 2025 AT 21:18From a pharmacovigilance standpoint, the FDA’s operationalization of SAEs through a risk-benefit stratification model is functionally sound, but the translational gap between clinical documentation and patient comprehension remains a critical barrier. The linguistic dissonance between ‘severe’ and ‘serious’-coupled with the absence of patient-centric risk narratives-creates a cognitive dissonance that undermines informed consent. We need narrative-based risk communication, not just checklists.

Stephanie Bodde

December 13, 2025 AT 22:33You got this! 🙌 Seriously, this post saved me from panicking over my side effects. I thought I was in danger because I was so tired-but now I know to watch for hospitalization, not just feeling crummy. Thank you for explaining it like I’m not a doctor.

Philip Kristy Wijaya

December 14, 2025 AT 14:37Let me be blunt: the FDA’s definition is a farce. A broken hip from dizziness is serious but a 48-hour migraine that ruins your life isn’t? You’re telling me that if I collapse from dehydration due to nausea but don’t get admitted, it doesn’t count? This isn’t patient safety-it’s a legal loophole engineered to shield manufacturers from liability while pretending to protect you. The system is broken. And you’re all just playing along.

Jennifer Patrician

December 16, 2025 AT 04:50Of course they define it this way. The FDA is owned by Pfizer. They want you to think you’re safe so you keep taking the poison. They don’t care if you’re in constant pain. They only care if you die or end up in the hospital. That’s how you know it’s a scam. Read the fine print. They’re hiding the real risks. I’ve seen it. They bury the data. You think your ‘mild’ side effect isn’t serious? Wait till your liver gives out in five years.

Ali Bradshaw

December 18, 2025 AT 03:12I’m from the UK and I’ve seen this confusion first hand. My mum had a drug reaction that left her dizzy for weeks. She didn’t go to hospital, so her GP said it wasn’t ‘serious’. But she couldn’t walk the dog or cook. That’s serious to her. The system needs to listen more to patients, not just to paperwork.

Annie Grajewski

December 19, 2025 AT 09:32So basically if you’re sick but don’t end up in the hospital it doesn’t count? Lmao. So my 3 days of vomiting and hallucinating from that new antidepressant was just ‘mild’? Yeah right. I’m reporting it anyway. And yes I spelled ‘hallucinating’ wrong. Sue me.

Norene Fulwiler

December 20, 2025 AT 21:00As someone whose family member was in a clinical trial, I can tell you this: the difference between ‘severe’ and ‘serious’ is the only thing that kept us from pulling them out of the study too early. We thought ‘severe nausea’ meant danger. Turns out, it just meant they had to give them extra meds. We learned to ask: ‘Will this send you to the hospital?’ That question saved us a lot of sleepless nights.